BOSTON, April 21 (JTA) — On a recent Wednesday afternoon, Stephanie Zable walked into the lobby of the Mudd Library at Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio, to meet her Chinese tutor. To her surprise, inside the lobby she found what she described as a giant wooden model of a synagogue — the Zabludow Synagogue. It was the name that really got her attention. “I realized from the name, Zabludow, that there was a family connection,” Zable, a first-year student at Oberlin, said in a phone conversation from the school, west of Cleveland. She was fairly certain that her father’s family was from Zabludow, in eastern Poland. But she called her father, Noah Zable, just to make sure. “My family never called it Zabludow, which is a newer, Polish name. The old name was Zabludova,” Zable said he told his daughter when she called him at home in Leawood, Kan. “It gave us a chance to talk about what I knew of our family.” “It was just, Wow,” Zable continued, describing her reaction to the model. “I realized that my great- grandfather prayed at this synagogue. I was reading about the women’s balcony and realized my great-grandmother sat and prayed there.” The Zabludow synagogue, built in 1637, was one of 200 wooden structure synagogues in Poland that were destroyed by the Nazis. The model and exhibit Zable saw is the brainchild of Laura and Rick Brown, a husband-and-wife art team of art historians from the Massachusetts College of Art in Boston. The Browns developed the Zabludow model project after they returned from a conference on preserving old wooden buildings in Poland in 2003. The model has also been on display at the University of Wisconsin’s Milwaukee campus and will be shown in other parts of the United States. The Browns are now part of a group of international Zabludow enthusiasts that includes representatives from a range of scholarly disciplines as well as Polish officials, craftspeople, history buffs and timber framers. The group hopes to build a full-size replica of the synagogue in Poland some day. “We see this model as a first educational step,” Laura Brown said. In constructing their model, the Browns’ students relied in part on a 1923 photograph taken by Polish students who were chronicling Poland’s wooden synagogues and whose work survived the war. The Browns’ project is shedding light onto a little known corner of the rich religious and cultural life of Poland’s Jews. That world was captured by Thomas Hubka in his book “Resplendent Synagogue” and by Marc Michael Epstein in “Dreams of Subversion in Medieval Jewish Art and Literature.” Hubka and Epstein both collaborated with the Browns on the model of the synagogue and on the reproductions of the allegorical paintings that cover the walls and cupola of the Gwozdziec synagogue, the subject of Hubka’s book. The 17th century is a “fascinating transition period, right there on the cusp of Chasidic Judaism, which has not been well explored,” said Sylvia Fried, executive director of Brandeis University’s Tauber Institute for the Study of European Jewry, which sponsored a lecture by Hubka and Epstein last winter. “We learn a lot about the role of popular mysticism, and the extent to which it is part of the fabric of Eastern European Jewish society,” she said. “From a 21st-century perspective, these buildings are exotic,” Hubka said, adding that some have three-tiered, hipped gambrel roofs. “It’s from a different time and place. It’s pre-modern and unlike anything we know.” “It tells through architecture the story of Jewish history, which was deeply rooted in Polish society on the one hand, and on the other, carved out a unique religious, social, cultural expression that you can see through the architecture,” Fried said. With the model, the Browns have created a focal point for families who trace their roots to Zabludow, and for the town’s few remaining survivors, whose emotional stories about the town and its synagogue now reach across generations and continents. Tilford Bartman, who lives in Holden, Mass., is descended from people who lived in Zabludow, and he’s put up a Web site about the town. He met the Browns in Poland in 2003, and discovered they lived less than an hour away from each other. “Zabludow was one of the first places Jews settled in eastern Poland,” and it was an important center in commerce and religious life, Bartman said. What drove Bartman, a forensic clinical social worker, to learn as much as could about Zabludow and create his Web site, at www.zabludow.com? “I realized the history of this 400-year-old town was in danger of being lost,” he said, and he felt an obligation to stop that process. Mina Bar-On, who lives on a kibbutz in Israel, got in touch with Bartman after she saw a photograph of herself on his Web site. The photo is of Bar-On as a young girl in Zabludow, where she lived before the war. Bartman learned that one of the other girls in the photograph, his aunt, was Mina’s best friend. In an e-mail, Bar-On wrote that although the prewar community used a newer building for daily prayer, on Simchat Torah “the old synagogue’s doors were opened wide, it was lit up inside and outside and everyone went with their children to dance with the Torah.” Bar-On also recalls stories about the large rock on the outside corner of the synagogue, as well as a legend about how birds saved the synagogue from danger during earlier pogroms. Laura Brown knows that much must happen before a full-scale replica of the shul can be built in Poland. The Polish government and individual Poles will have to embrace the project. Brandeis’ Fried says, “The model changes the conversation and changes the image to how Jews lived and how they expressed themselves. And it does so through art.” When she worships at her own synagogue, Fried says, she looks up at the ceiling and begins to think about the structure in which she prays every week. “The engagement with this aspect of Jewish history — it’s not just about roots, but it also brings us to explore our life today,” she says.

Model wooden Polish shul stirs memories

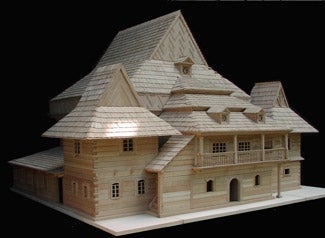

The Zabludow Synagogue model. (Courtesy of Handshouse Studio )

Advertisement