NEW YORK (JTA) — Rabbi Stephen Wise and Nahum Goldmann convened the founding plenary assembly of the World Jewish Congress in Geneva, Switzerland, in August 1936, in the shadow of ever increasing persecution of Jews in Nazi Germany. It was the first time that Jewish leaders from different countries joined together as a decidedly activist and political body, rather than a philanthropic one, for the express purpose of representing Jews around the world.

Since then, the WJC’s sometimes hotly debated endeavors have included obtaining reparations and restitution for Holocaust survivors, repairing frayed ties with the Catholic Church and publicly countering resurgent neo-Nazi parties and movements in various European countries.

About two years ago, when WJC President Ronald Lauder and CEO Robert Singer first told me they wanted to publish a comprehensive history of the WJC’s first eight decades, we rapidly came to the conclusion that such a book had to reflect the diversity of voices that has always characterized the organization and, indeed, the Jewish people.

Instead of asking a single historian to write an academic, chronological study based primarily on archival research, we opted instead for a mosaic, with chapters about specific episodes or themes written either by individuals who had personally participated in the WJC activities and accomplishments in question, or by scholars with expertise in the subject matter.

The result, “The World Jewish Congress, 1936-2016,” is not just a history of the preeminent international Jewish human rights organization. It is a reflection of the tensions, energies and accomplishments that have characterized global Jewish activism in the 80 years since WJC came into existence.

Thus, author Gregory Wallance chronicles the WJC’s rescue efforts during the Holocaust years, and legal historian Jonathan Bush discusses the invaluable assistance provided by the WJC’s legendary attorney Jacob Robinson to the prosecutors at the post-World War II International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg.

Monsignor Pier Francesco Fumagalli, vice prefect of the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, recalls the pioneering role of the WJC’s Gerhart Riegner in crafting a new Catholic-Jewish relationship. Gregg Rickman, who led the U.S. Senate Banking Committee’s examination of Swiss banks and their treatment of Holocaust-era assets during and after World War II, describes how the WJC and its then president, Edgar Bronfman, spearheaded the campaign to force Swiss banks to disgorge more than $1 billion they had wrongfully withheld from Jewish Holocaust victims and their heirs.

Eli Rosenbaum, the longtime head of the U.S. Justice Department’s Office of Special Investigations, who oversaw the WJC’s exposure of the Nazi past of a former U.N. secretary-general and Austrian presidential candidate, gives a fascinating insider’s account of the notorious Kurt Waldheim Affair.

Natan Lerner, the director of the WJC’s Israel branch from 1966 until 1984, writes about the WJC’s relationship and interactions with the State of Israel, while Evelyn Sommer, chairperson of the WJC’s North American section, depicts the instrumental part played by the WJC in fighting against and ultimately rescinding the U.N. resolution equating Zionism with racism.

Other chapters in the book are devoted to the organization’s successful diplomatic negotiations on behalf of Jews from North Africa in the 1950s and ’60s; the moral and intellectual debate over the post-Holocaust future of Jewish life in Germany, and the controversies surrounding the plight of Soviet Jewry. Singer describes the organization’s array of present-day programs and activities, including major initiatives in fighting anti-Semitism around the world and the ever-increasing efforts to delegitimize the State of Israel.

For the past 10 years, the WJC’s persona has been shaped primarily by Lauder, who has imbued the organization with a distinct sense of purpose focusing on the challenges confronting the Jewish people and Jewish communities across the globe in the 21st century, as well as, perhaps most importantly, on providing opportunities for the young Jewish leaders of tomorrow.

“There is an old Hasidic tradition,” Lauder writes in the concluding chapter, “that inside every Jew there burns a flame. Sometimes that flame is obscured, and the person can’t see it. But it is always there, it is always burning. All you have to do is dust off your heart and you will find it. … And this is the job before us now. We have to help our children and our grandchildren dust off their hearts. We have to help them rediscover that Jewish flame inside them.”

The book also contains speeches delivered by Lauder’s predecessors at critical moments in the recent history of the Jewish people.

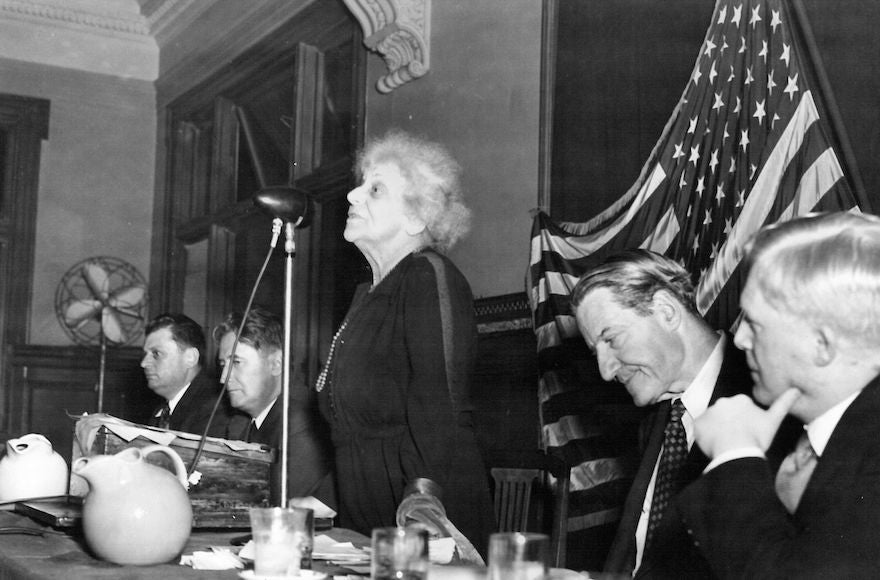

“We Jews do not profess to be neutral as between democracy and dictatorship,” Rabbi Wise declared prophetically at the WJC’s War Emergency Conference in Atlantic City, New Jersey, on Nov. 26, 1944, “as between freedom and enslavement, as between religion – which is the worship of God the Father and the doing of justice to one’s brother man – and … idolatry, which is the worship of man and the unjust enslavement of one’s fellow man.”

“The State of Israel requires a strong Jewish Diaspora,” Goldmann said at the WJC’s second plenary assembly in Montreux, Switzerland, on June 27, 1948, “just as the Jewish [Diaspora] requires the State of Israel. The greatest reserve line in support of this Jewish state … will for years be a strong and united Jewish people, ready to support it morally, spiritually and practically. The existence of the State of Israel, on the other hand will … give the Jewish people a voice among the nations of the world, and put an end to the anonymity of Jewish existence.”

These words remain as relevant for us today as they were when they were first uttered. It is our hope that the WJC’s past accomplishments will continue to be a foundation for its future, and that “The World Jewish Congress, 1936-2016” will become an essential resource not just for an understanding of the WJC, but for anyone interested in Jewish political history of the 20th and early 21st centuries.

(Menachem Z. Rosensaft is general counsel of the World Jewish Congress, and teaches about the law of genocide at the law schools of Columbia and Cornell universities. He is the editor of “The World Jewish Congress, 1936-2016.”)